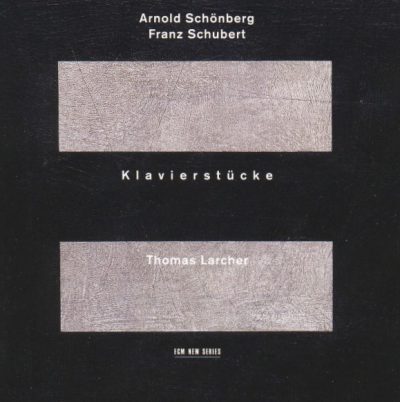

Thomas Larcher: Arnold Schönberg, Franz Schubert: Klavierstücke

Thomas Larcher (piano)

© ECM 1999

Works

Arnold Schönberg: Klavierstücke op. 11

Arnold Schönberg: Sechs kleine Klavierstücke op. 19

Franz Schubert: Klavierstücke D 946

Franz Schubert: Allegretto c-moll D 915

The Texture of Darkness in the Piano Works of Schubert and Schönberg

Gert Jonke

The pieces played here are night pieces. I am simply stating this. Not those kind of night pieces which some nobleman commissioned as background music for evening entertainment, or, as in the case of Goldberg, who ordered those famous variations from Johann Sebastian Bach to help his employer cope with his insomnia as a sort of custom-made pyjama. The present works are rather musical descriptions of states of being and narratives about the nature of darkness in former nights, and how people of today can deal in a somewhat practical manner with this completely unknown, different kind of darkness because darkness of this sort does not exist any more, at least not in the populated parts of the globe. This kind of darkness has actually in a way died out and should therefore be placed on the list along with all those plant and animals which are lost forever and thus belong to those unknown remaining genera of species which at least do not occur in a living state–and that is not just because of or since the introduction of electric street lighting.

The darkness in those days was denser in texture and thus more intense that today because nowadays we are confronted with a totally slipshod emergency solution for night darkness, which could at best be called a coma perforated by a ubiquitous mould of decomposing light.

The tonal languages of Schubert and Schönberg convey this ‘old’ darkness with such congruity that the arrangement of the program on the CD is duly legitimized, and our pianist does not have to persuade the listener to accept the pieces in this ‘gentle concubinage’. The music provides an additional allure in that the listener can observe exactly how the pieces of these two composers, who are from such different epochs, just plain ‘like’ each other…

Schubert once said that in at that time most people believed that the distances between the individual houses and villages were longer in the night than during the day because each dusk demanded that its subservient shadows become longer and longer in order to stretch towards the tardy sun and shove her through the boundary of the horizon away from the day; whereupon the already breaking night with its accruing streams of shadow culminating in ultimate darkness, pushed the houses, villages and the smaller district towns far apart, sometimes violently. This had the consequence that the streets and paths which connected the houses, villages and district towns were also forced to lengthen. Sometimes a street or path between two villages was stretched so far that it snapped in the middle like a rubber band.

If this happened to someone who was walking in the night, that is, that a path or street disintegrated right under his feet, he would have no other recourse than to wait until the dawn in order to find the lost link, if he was lucky, and thus get home in more or less one piece.

Schubert himself, however, tended to believe that it was the texture of the darkness which caused the distances to be larger in the night in comparison to the shorter ones of the daytime. It was the denseness of the darkness in those days which did not let the traveller continue on his way, which is why the night wanderer often treaded in one place on the path without noticing that he was doing so, and that frequently the wheels of the stagecoach turned in place without the postilion’s realizing it. Thus all the paths seemed significantly longer in the night, at least double to long and so broad as the same stretch in the daytime, or even longer, depending on the intensity of a particular darkness’s density.

Arnold Schönberg, on the other hand, described the texture of darkness in his music as follows: As darkness is falling, a man leaves his house in order to visit a man or a woman friend in another house which is not too far away, not anticipating any particular problems in connection with passing through the darkness since he has successfully taken this route and back many times before. The man walks and walks without anything striking him as being odd since he, of course, knows that in the night the distances seem at least twice as long as during the day due to the intense darkness. So he keeps on going and still nothing seems strange to him until it seems to him that all of sudden dawn breaks much too early.

As the contours of the lightening landscape become increasingly clear, the man, who has continued walking, sees he is still very far from the house of his man or woman friend. He thinks that in some strange way it seems much too far away, and he involuntarily looks around. He sees that he is standing with his back not very distant from his own door; in fact, there stands his own house, the one he left last night, only a few hours ago, in order to go to the other house where his man or woman friend lives, which is not far away from his own house and which (that is, the house of his man or woman friend which he did not get to last night) now gradually emerges from the remnants of the diminishing dawn and seems to purposely float quite near to his face before it soon comes to rest at a place nearby. Thus the house that he had wanted to go to the night before but had not been able to get to, was this morning lying right before his eyes.

Quoted from booklet to the CD Thomas Larcher: Arnold Schönberg, Franz Schubert: Klavierstücke